Tank Containers and Compatibility

As the politician in the USA nearly said when he wanted to become president, “its compatibility, stupid”! If there is one thing, we have all got a duty to get right when working with the ISO tank container it is compatibility. This is so important. I like to say that the difference between normal dry box container shipments and shipments in tank containers is that the tank container shell is the actual containment for the goods being shipped. There is nothing else between the >8 billion people in the world and the dangerous goods being transported in a tank container and the amazingly small thickness of the walls of the tank shell. For the typical tank container intended for the transport of liquids, the thickness in the stainless steel we use to construct them is quite a lot less than 5 mm – remarkable!

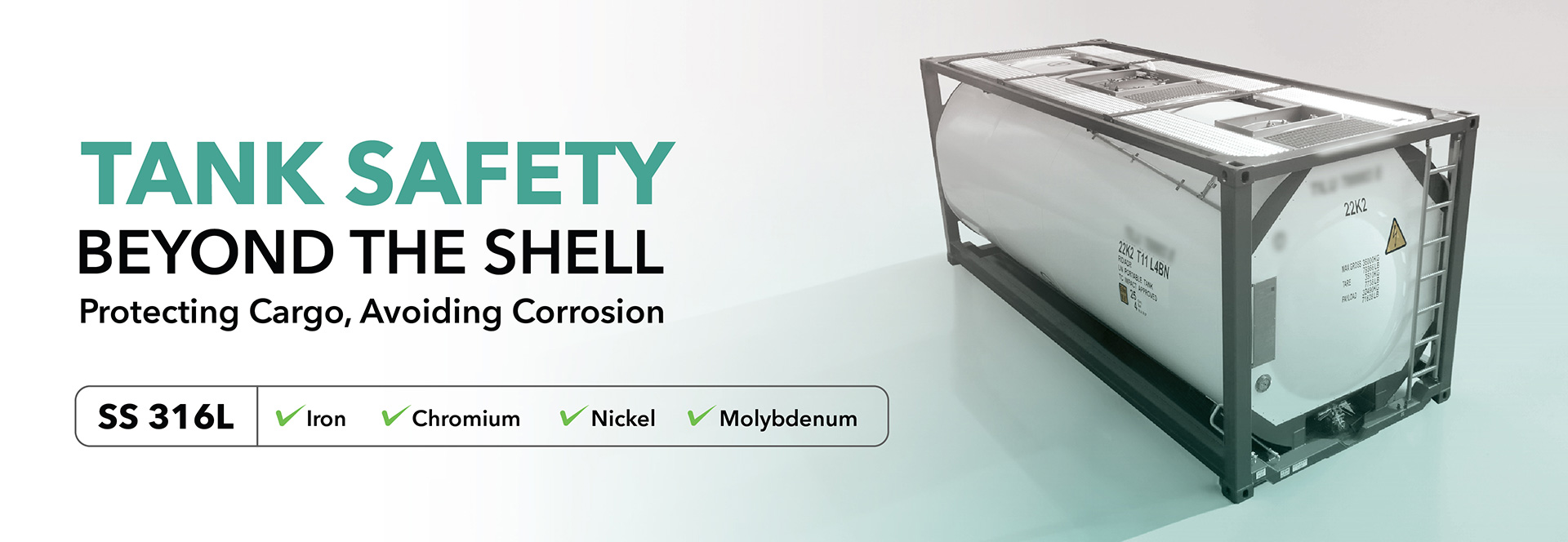

The shell of the typical tank container intended to transport liquids is fabricated in a grade of stainless steel commonly known as “316L”. This term is derived from a USA standard for stainless steels. There are many different grades of stainless steel. So, what is, exactly, stainless steel? Well, the first thing to say is that the typical stainless steels we use to manufacture tank containers from is far from stainless. These grades, rather, are easily stained by some of the substances we are asked to carry leading potentially to heavy cleaning costs to prepare them for the next cargo. Rather the better term is “rust proof” or “inoxydable” as they are described in French.

Stainless steel may be described as an “alloy” – a mixture of two or more metals. It starts with adding the metal chromium to iron. A typical stainless steel used for tank containers has around 18% of chromium in it. You can then carry on adding all sorts of extra ingredients to this mixture to improve the performance of the steel in different ways for different purposes. Another key ingredient we add to the grade of stainless steel we typically use for the manufacture of tank container shells is the metal nickel. The grades we usually use for tank containers have around 12% of this metal in the alloy. Nickel, usually the most expensive ingredient in stainless steel, provides a big help in achieving compatibility – no corrosion – with many of the substances transported in tank containers. There are several other ingredients in the steel we use for tank container manufacture such as molybdenum. This also helps to achieve compatibility of the tank shells, pipework, valves and so on as well. The more nickel and molybdenum in the steel the better as far as compatibility is concerned.

It is essential for the performance of stainless steel in other respects for it to contain carbon. We must have a certain amount in the stainless steel we use to give it strength. However, this can potentially reduce the degree of compatibility with the substances we want to carry in our tank containers. A 316L stainless steel will have less than 1% carbon in these alloys – the less the better for compatibility consistent with ensuring the stainless steel has sufficient strength.

Some substances may be naturally compatible with this type of stainless steel. Other substances may be compatible with stainless steel providing there is a “passive layer” on the surface. A passive layer forms by itself if the stainless-steel plate is left out in the air as oxygen reacts with the chromium in these alloys as the air flows over these surfaces. However, when the tank shell is formed by rolling the flat plates into the cylindrical shape and when the “dished ends” are formed and these sections are welded together to form the complete tank shell, this natural process is lost. In such circumstances it is wise after construction or after, for example, the scrubbing of the inner surfaces to remove resinous skinning forming on the shell by some of the substances which we carry.

Nevertheless, there are many substances which we transport which can cause corrosion – often in a form called “pitting” – of this stainless steel. The IMDG Code governing the transport of dangerous goods world-wide by sea and other modal dangerous goods regulations call for there to be compatibility between the substances being transported – substance(s) carried must not affect the tank. Shippers, when they sign the Dangerous Goods Note guarantee this. They also guarantee that the substance(s) carried will not attack any pipework, valves, manlid seals, O-rings and other gaskets used on the tank. The IMDG Code also calls for shippers to ensure that it must not be possible for the substance(s) carried to pick up a contaminant from what the tank, its pipework, valves, gaskets, O-rings are made from which could trigger a dangerous reaction with the substance(s) transported, for example, catalyse a dangerous polymerization reaction. How many shippers consider this when they sign the dangerous goods note.

One of the biggest enemies of stainless steel is chlorine. This element, even if only in tiny amounts in the substances transported may cause pitting. Every step possible must be taken to avoid even the slightest trace of the presence of chlorine. It may be present, perhaps, because hydrochloric acid is used in the production process and is not 100% removed before loading our tank containers. It may be present, perhaps, because “town water” has been used in the manufacture of the substances transported to which a source of chlorine has been added to purify it for humans to drink. The corrosion risk is exacerbated if the substance(s) to be loaded are loaded hot, above ambient temperature. Whatever the case every step possible should be taken by shippers to eliminate the risk of pitting to tank containers even with so-called “non-hazardous” substances.

Remember, there is no such thing as “non-hazardous”. The term is not defined in law nor is this a true scientific statement. Remember you can even drown in a substance like water”.

Roy Boneham

IMDG Expert